Forgotten Basilicata

Year by year Italy is one of the top five visited countries on the planet. As well, the Institute of International Education lists it as the second most popular study abroad destination for college students just behind the United Kingdom. Although this is great news for Italy’s economy it is not always the best of news for travelers to the country’s leading tourist destinations. Throngs of visitors crowd into Piazza del Duomo year round to take in the brilliance of Brunelleschi’s dome. In Venice, the line to get into St. Mark’s Basilica wraps around the square during the height of the summer season. Along the Amalfi Coast in Campania, sunbathers are packed next to the Tyrrhenian Sea like a giant game of Tetris. Yet while Italy is winning the tourist game not all of its regions are benefiting.

The typical tourist guidebook to Italy shows a familiar voyage stretching back to the 17th century when northern Europeans on the Grand Tour ventured south to bask in the splendor of antiquity and get reacquainted with Mediterranean culture. Stop offs at Venice, Lake Como, the Cinque Terre, Assisi, Siena, Rome and Positano would be familiar to Grand Tour travelers of earlier centuries. If a tourist comes to Italy and complains about the crowds of the high season, their experience is reflective of channeled marketing in which a few select cities and destinations become more and more popular while whole swaths of the country remain very much unexplored by foreigners. For instance, the ‘spine of Italy’ which runs along the eastern coast of the peninsula from just south of Ravenna to the tip of Salento is not well trafficked even though it has some incredible Adriatic vistas that rival burgeoning Croatia. The toe of Italy, Calabria, has some of the most splendid and ancient towns in Italy as well as some of the country’s best cuisine. But these are easy examples. This installment of Honestly Italy will take you to the least desirable and most unpopular region in modern Italy and let it shine like the must-visit destination it is. Welcome to the ‘instep’ of Italy. Welcome to Basilicata.

Storia

The region of Basilicata lies in the far southern reaches of Italy wedged between Puglia and Calabria with the Ionian Sea to its south. It has always been a rough existence for those living on this part of the peninsula with a limited transit network and few access points to the sea. This isolation is compounded by the fact that over 90% of this region is mountainous. For centuries these parts were seen as Italy’s ‘Wild West’ and is presently the least densely populated region in the country. The hot summers, rough terrain, and lack of effective transport into Basilicata until the 20th century meant the region developed at very different pace.

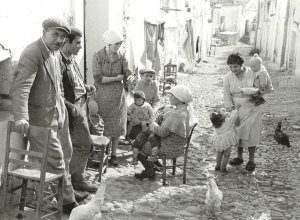

When Enrico Pani Rossi visited the towns of Basilicata in 1868 as part of post-unification survey he described a people living hand to mouth and existing in a state that seemed unchanged since the days of Byzantium. His written account also gained infamy for not only its description of the region’s stagnant economic outlook but also the cultural practices of its people. For instance, religious rites seemed unchanged since the days of the fading Roman Empire and only small aspects of Christian worship had fused with ancient customs. As well, there was distrust amongst its people not only of catholic institutions but the national government as a whole. The hardships of Basilicata grew worse in the 1880’s when Italy suffered a financial crisis. During the period from 1881 to 1921 over 10% of Basilicatans left the only home they had ever known and sought lives elsewhere outside of Italy.

The rise of fascism in the 1920’s did not create any new opportunities for the people of this region but only formed new headaches. The country was further isolated from the national economy since Benito Mussolini did not think the mission of ‘national progress’ should apply to the meager people of Basilicata. Furthermore, political enemies of the fascist state were exiled to Basilicata in the hope that this was a form of sending despised portions of the population off to ‘Italy’s Siberia.’

One of those castoffs to Basilicata was Carlo Levi. He was an anti-fascist activist and doctor living in Torino who was arrested and deported by the fascist government to the towns of Grassano and Aliano in 1935. His reflections in his masterwork, Christ Stopped at Eboli, not only showed the economic plight of the people but also their determination, generosity, and graciousness. Carlo Levi’s reporting also showed the despicable ways by which the national government (both fascist and prior) treated as well as viewed the people of the region. Christ Stopped at Eboli therefore showed not only the resilience of the Bascilicatan people but also what policy changes needed to occur in the decades to come.

In 1951, over 5 years since the end of the war over 75% of workers were still involved in a meager agricultural trade. This was set to change drastically. At the start of the 1950’s the Italian Miracle sent tens of thousands of southern peasants northward to the burgeoning ‘industrial triangle’ of the north (Torino, Milan and Genoa) for work in rising factories. At the same time, gas deposits were discovered in their home region and an energy boom created new job opportunities for the people of Basilicata. The rise in the standard of living increased further with the growth of service and manufacturing job centers throughout the region. This was capped off in the 1990’s by the opening of the FIAT assembly plant in Melfi.

So we arrive at the summit of modern Basilicata: a region of two different worlds. The modern era has brought train lines, jobs, and services that a generation ago would have seemed otherworldly. Today only 15% of people from this region hold jobs in agriculture. Yet, as one traverses the ancient towns of Basilicata, one is left with the sense of a people who have not left their past behind.

Viste

When traveling around Basilicata, a perfect illustration of how the region blends its history into contemporary life is the city of Matera located 25 miles from the Ionian Sea. The district of Sassi in Matera is an incredible UNESCO World Heritage Site with homes and churches dug out and constructed from ancient volcanic rock. From Piazza Duomo in the old city center there is an incredible vista of the city as centuries old dwellings seem to tumble down the city’s hilly terrain.

Further inland are the towns of Castelmezzano and Pietrapertosa. Both villages cling to the edge of scenic vistas, which offer unparalleled views of Basilicata’s iconic mountainous terrain. Both have quaint historic centers and were named by the National Association of Italian Municipalities as two of the most beautiful villages in Italy. What makes the journey to these towns even more special is the Volo dell’Angelo or ‘flight of the angels,’ a suspended zip line that connects Castelmezzano and Pietrapertosa by whisking you over the bucolic valley. Try finding that type of transportation in any Tuscan hill town!

Another village that gives any quaint Tuscan hill town a run for its money is Acerenza. The town’s centro storico is a blissful twist of old lanes capped off by its impressive Duomo. The high perch offers not only great cuisine from Basilicata but also incredible views of the valley surrounding the town.

About an hour’s drive from Acerenza is the town of Venosa which has its origin dating back to its time as an ancient Roman settlement. The archeological park on the eastern edge of town tells this story with the ruins of thermal baths and an amphitheater. Venosa is also well known for the region’s sole DOC wine called Aglianico del Vulture (a cousin of Lacryma Christi). The wine has gained advocates in recent years and is one of the reasons Basilicata is starting to be seen as a potential tourist destination.

The ancient remains of Venosa are also complete with its own complex weave of Jewish catacombs which is evidence of this group’s settlement in the area around the last centuries of the Roman Empire. Besides its slew of historic sites Venosa has an incredibly charming old city center with windy cobbled lanes and piazzas that make you wonder why more visitors to Italy haven’t ventured to this part of the peninsula.

Further inland is one of the most iconic castles in all of Italy: the Castello di Melfi. Built during the Norman conquest of southern Italy during the 11th century, the castle is incredibly intact inside and out. Climbing the ramparts offers visitors fantastic views of the surrounding region and town.

When the hilly inland of Basilicata has been well trodden, the coastal areas of this region offer an easy respite. Along the Tyrrhenian coast, the town of Maratea offers breathtaking views and sun for a fraction of the crowds of farther north in Amalfi. The historic town center is perched above the sea with its sandy beach set down below. It is the perfect way the end a journey through this forgotten land.

Cibo

While there are many sites to take in during a stay in Basilicata, the real destination is its cuisine. Over recent years, the attraction of recreating cucina povera or ‘peasant cooking’ has picked up a great deal of steam the world over. The origins of cucina povera come from a very real place where southern peasant created delicious meals with limited but fresh ingredients. Nowhere is this more on full display than in Basilicata.

The legacy of this region’s gastronomy stretches back centuries. So much so that the first mention of pasta was written by the ancient poet Horace who was born in Venosa during the 1st century BC. From these humble beginnings the people of Basilicata built a unique cuisine that has gained converts from other Italian regions. An example of this is the lucanica sausage which originated during Roman times and is still an iconic staple of the Basilicatan diet. The dried version of this meat is flavored with wild ginger (a favorite seasoning in this region) and hung to age for up to a year. The end result is the Basilicatan version of soppressata.

Another famous product from this region is caciocavallo cheese. It’s a sheep’s cheese which is balled up and hung like a horse’s saddlebags (hence the name) to age. The finished product tastes like a more pungent version of provolone cheese with a similar consistency.

The art of aging does not only apply to meats and cheeses. The delicacy of pepperoni cruschi is thin sweet peppers which are dried and aged in the sun then fried in olive oil. They can be eaten on their own as a snack or added to compliment a Basilicatan dish.

One of those recipes is cavatelli con peperoni cruschi, cacioricotta, e mollica di pane fritta. The long name basically equates to the following. Bread crumbs are fried in olive oil with chopped up peperoni crushi. Then, pasta is mixed in and topped with a local sheep’s cheese called cacioricotta. The result is a delicious portrayal of quintessential cooking from an oft-forgotten region and is the perfect complement to a glass of Aglianico del Vulture. Imagine enjoying this meal in an ancient piazza surrounded by locals, far from the thongs of tourist. This is Basilicata. This is today’s Italy.